Easter, known in Ukrainian as Velykden, is a holiday when Christians all over the world celebrate the victory of life over death and enjoy a spirit of wonder as they mark the resurrection of Jesus Christ. The sacredness of this event imbues everything around it with holiness, and Ukrainians' life around the holiday reflects this deeply.

In preparation for Easter, we have gathered some interesting facts to know about how the holiday is prepared for and celebrated in Ukraine.

Easter is celebrated in Ukraine both by the Julian calendar (for many Orthodox Ukrainians) and the Gregorian Calendar (for Catholic and Protestant Ukrainians). Since these calendars have Easter on different dates, it means Ukraine usually has two Easters, though sometimes dates coincide.

Both days are commemorated equally, as shown by various aspects of the festivities.

On both days, elegantly dressed Ukrainians walk to their local churches bearing baskets of food to be blessed with holy water. Ukrainian supermarkets feature Catholic Easter chocolate eggs and bunnies alongside products for Orthodox Lent. A myriad of decorations adorn the shelves, while village farmers flock to towns to sell fresh poultry and rabbit.

National television broadcasts both church services, and the President extends Easter greetings to religious Ukrainians on their respective days.

The majority of religious Ukrainians identify themselves as Orthodox. Many of them observe Lent, a 40-day period of self-denial and more pious living, which marks Christ's 40 days in the desert. It is the longest of religious Lents.

This period is intended to prepare people spiritually for Easter so it would be met with a clear head and closer to God. Religious Ukrainians spend Lent reading the Holy Bible, praying more than usual, preventing evil thoughts from their mind, and following the commandments more diligently.

As we mentioned, Lent also changes people's diets. In order to better elevate the soul above corporeal desires, religious Ukrainians abstain from eating animal products during Lent.

Good Friday is the apogee of Lenten self-denial,

as it marks the day when Christ gave his life for humanity's sins. The faithful usually honor the day by not eating at all.

Although Lent is directed towards inner spiritual matters, Ukrainian cultural traditions emphasize preparing the external setting for Easter during this period.

Before baking paska the house should be all capitally cleaned up and decorated. In earlier times, the walls should also be whitewashed. Ukrainians take their rushnyky (embroidered towels) out of the chests (and now they extract them from the closets) to hang them around the house, typically near the icons.

Paska is a Ukrainian special Easter Bread. We won't delve into recipe nuances here as it is worth the separate article. However, we'll shed light on its preparation.

Paska is always baked by women in Ukraine. It happens either on Maundy Thursday or on Holy Saturday. Both days are close to the Day of Resurrection, with a Good Friday between them, whilst cooking on Good Friday is strongly forbidden.

Ukrainian women prepare for it mentally, praying before and during baking, and physically, as it is a long process.

Here are a few lines describing how it was in the 19th century, written by young Pavlo Pototskyi, the Ukrainian military, and historian:

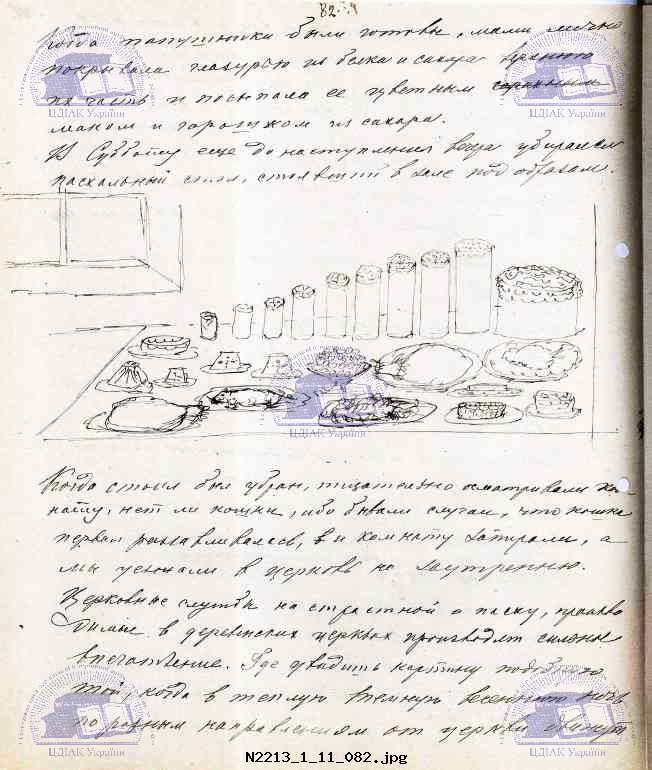

"A plethora of food was being prepared. More than ten papushniki (the variation of paska) were baked, ranging from five-quarters of an arshin (old unit of measurement equal to 28 inches or about 0.7 m) in height and six inches in diameter, gradually decreasing to two-quarters in height and three inches in diameter... As these giants stood in the oven, my mother spent the night in the kitchen.*

One time I didn't see my mother for so long because of all this work that I missed her and decided to go to the kitchen to see her. So unfortunate was I that I entered the kitchen right as the best papushnik was being taken out of the oven and was lying on a down jacket to prevent it from settling...

She waved her hands at me and shouted at me for coming in, and ordered me to quickly close the door. I soon found out that this papushnik was torn in the middle... I was hurt that I had caused trouble for my sweet and kind mother."

As Pototskyi makes clear, paska baking is a special women's ritual

for which they expect to be left alone so that they can concentrate on preparing both the bread and themselves for the holiday.

Paska breads baked with love from within and from God are considered holy objects. A Ukrainian tradition holds that their crumbs should be collected instead of discarded, and some people add them to the soil for a good harvest.

Pysanky (the plural of pysanka) are specially-decorated Ukrainian Easter eggs and the holiday's important attribute. The oldest pysanka ever found was 950 years old

and was excavated by archeologists in Volyn Oblast. These decorative eggs are known to have been common during the times of Kyiv Rus when they were made of stone or clay.

Eggs, in general, symbolized fertility and the sun before Ukraine was christened. However, the scientists still discuss what the first meaning of pysanky was. As they were made shallow and with a rattle inside, some argue they were toys, while others state they had ceremonial and decorative functions before Christianity.

Nevertheless, there are pysanky out of goose eggs, made in the 10th century, which were certainly not toys.

The ancient method of painting pysanky with curly brackets is still used for painting Ukrainian pottery. The technique is now called flyandrivka.

Mykola Sumtsov, Ukrainian ethnographer and academic from Ukraine's National Academy of Sciences, collected many folk stories connecting pysanky and krashanky (mono-color-painted bird eggs also popular on Easter) to Christ.

Among those is the story about Jews, martyring Jesus to the state when his body was 'painted' (beaten with whips, thus 'painted' by wounds). Sumtsov also mentions a legend in which normal eggs turned red

in the eyes of those who did not believe in the resurrection of Jesus, serving as proof of it.

Nowadays, painting eggs is a tribute to our past and to the way our ancestors saw the world. The process brings Ukrainian families together to delve into the symbolism of many possible elements that can be depicted on one egg.

Ukrainian pysanky were the first canvas upon which legendary Ukrainian painter of Cossack origin Illya Repin painted as a child, and they have become one of the many iconic symbols of Ukrainian culture recognized throughout the world.

Well, imagine all pasky have been baked, all the pysanky and krashanky have been decorated, and all dishes have been cooked. It is Velykden morning, and Ukrainians begin it with Khrystos Voskres! (Christ Has Risen!), to which they respond Voistynu Voskres! (Indeed He Has!).

This ritual is called khrystosuvannya and may also be followed by three kisses.

These salutations are heard in the streets between strangers and loved ones alike. Even those who do not consider themselves religious join in the tradition.

But first things first: on Easter morning, Ukrainians go to church to consecrate baskets of food with holy water before enjoying their contents. Some go to church late on Saturday evening to begin their Sunday with everything prepared and finally break their fast.

As people arrive, they congregate around the church, laying their food baskets on the ground and lighting candles. The priest, while reciting special prayers for the blessing of the land and other provisions, consecrates the brought offerings.

Here's the piece about the precious tradition from the magazine Our Life, a periodical created by Ukrainian women in exile, written by Maria Slusarchuk in 1956:

On Saturday evening, I began preparing by lining the basket with an embroidered cloth. In the center, I placed a paska, surrounded by sausage, peeled eggs, and two pysanky. I made sure cheese, butter, salt, and horseradish were included, along with a candle. Everything was then carefully covered with periwinkle leaves and topped with the finest embroidered tablecloth I owned. Families gathered beneath the church at the appointed hour, chatting to pass the time while awaiting the consecration.

Although Maria wrote back then that she was worried about these traditions disappearing, the tradition remains very popular today among Ukrainians of different ages. Only after this ritual does the festive breakfast begin, always with pieces of paska and eggs.

It is no secret that the Soviet Union sought to erase religion and its traces throughout the lands it controlled. Thus, Soviet authorities fought to suppress the celebration of Velykden.

At first, different common activities suspiciously coincided with the date of Easter to distract people from the event. For example, researcher Tetyana Hruzova writes that in 1932, the League of Militant Atheists organized a competition between working brigades on Easter.

Here is an excerpt from her research:

"[Those competitions] encouraged people to go to work, and thereby demonstrate the 'advantages' of socialism over religion.The headlines of the articles speak eloquently about this campaigning and propaganda work -- 'Striking work on the days of Easter,' 'Our holiday is a holiday of work,' 'Hundreds of sown hectares are the best answer to churchmen.'"

From other sources, we learn about subotniky organized exactly on Holy Saturday, before Easter Sunday, so that people would have no time to prepare.

But it did not stop there. The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was banned, and its followers were persecuted. Others visiting church were kept in fear. Children were even forced to keep the fact that their families had baked pasky a secret, tells Olesya Stasyuk, director of the Memorial to the Victims of the Holodomor in Ukraine.

Maria Slusarchuk also touched upon this problem in her writing from 1956:

It appears that no other nation possesses Easter customs as beautiful and refined as ours. Perhaps that is why the red occupier is so intent on eradicating all traces of them.

But the Ukrainian Greek Catholic church existed underground, people secretly took holy water to consecrate their festive food at home themselves, and even managed to covertly hold confession in writing.

The fact that public Easter celebrations returned immediately after Ukraine gained independence shows it was never erased from Ukrainian identity.